Dozens of American children are abducted to Japan every year—not by strangers, but by parents after messy divorces. Nathalie-Kyoko Stucky and Jake Adelstein report Updated Jul. 11, 2017 7:19PM ET / Published May. 19, 2013 4:45AM ET

Japan has a child-kidnapping problem. It’s not strangers snatching the kids on the playground or at the bus stop; the problem is that when a Japanese national divorces a foreigner overseas, he or she can abduct their children and bring them back to Japan, and the law ensures that the parent left behind has no rights to see the children or take them back home. The U.S. State Department reports that there have been over 100 such kidnappings since 1994, but according to a source, the number is closer to 400. Within Japan itself, divorce often means that one parent may have little or no access to the child. Japan’s inability to deal with child abduction partly stems from archaic family law in Japan that does not recognize joint custody. It’s a winner-take-all system. The law makes it almost impossible for the other parent to even meet the child, if the Japanese partner objects.

“Once the child is on Japanese soil, if the foreign parent tries to take them back to their home country, we have to treat him or her as a kidnapper—unlessthe Japanese courtshave clearly given them custody,” a police officer from Tokyo told us. “Most of the time, we imagine the Japanese parent is shielding the child from domestic abuse or a poor living environment. Maybe sometimes the foreign parent is actually trying to rescue his or her child from an abusive Japanese household, but we can’t make that judgment. The non-Japanese trying to take back their child is the criminal in most cases. The law is the law.”ADVERTISEMENT

After 30 years of international pressure, Japan’s National Diet is expected to endorse the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction this month and approve necessary legislation possibly by the end of the year. At present, 89 countries are members of the Hague abduction convention, which went into effect in 1983. Japan is the only G8 country that is not a member.

If the Diet ratifies the treaty by the end of May, as predicted, it would extend custody rights to non-Japanese parents whose children have been taken to Japan by their former spouses. After ratification, the Japanese government will have to take steps to ensure that the treaty is actually upheld. Under the convention, the parents of abductees will have a legal framework to request their children be returned. However, the convention prohibits returning children to the country of residence if they face grave danger, including domestic violence. Questions remain as to the burden of proof that will be required for Japanese nationals who refuse to return the children, using allegations of “grave danger.”

The U.S. State Department has been conducting surveys on the number of abducted American children since 1994. The numbers are difficult to assess because not all parents report abductions to the authorities. Victims of child abduction are hard to track officially, because Japan and many countries do not consider it a vital statistic. Also, child abduction by a parent is not considered a crime in Japan once the family court grants the sole custody to one parent. However, some researchers have been keeping track of the numbers by gathering information from town-hall meetings and correspondence with the families of the abducted. According to one knowledgeable source, between 1994 and 2012, there were 278 cases involving 386 American children taken back to Japan.

“There are no official numbers,” explained Yuichi Mayama, a member of the Diet. “Even we lawmakers, when we tried to ask the government for the exact number of cases, got no real answer. The answer we got was that probably after the Hague Convention comes into effect, it may be possible to track the numbers.”

“Simply because a marriage breaks down, that does not necessarily imply that the children should lose one of their parental relations,” said John Gomez, chairman of the recently founded nonprofit organization Kizuna Child-Parent Reunion. He notes that many pediatricians and child-care experts assert that children thrive when they have relationships with both of their parents, even after the marriage is over. But there is a concept in Japanese society that after a divorce, it is natural for one parent to give up the right to raise the child. Article 766 of Japan’s Civil Code states that a family court should decide who will have custody over a child. The extent of visitation and other means of contact between the child and their parents are also made by the court. There is no joint custody in Japan.

Experts estimate that each year close to 150,000 divorced parents in Japan lose contact with their children. Some choose to do this; most have no say in the matter. While it’s obvious that international divorce in Japan is often an ugly affair that splits children from their parents, it should also be noted that domestic divorce cases are often as bad.

Takao Tanase, a lawyer who is a law professor at Chuo University in Tokyo, notes that Japan does have a criminal clause declaring child abduction a crime, and cases of domestic abduction are not unknown. “However, the first abduction is usually not treated as a crime,” he said. “After a parental dispute, once the de facto custodian is designated by the Japanese family court, the left-behind Japanese parent can be arrested by the police if he or she tries to take back the child from the custodian parent.”

In September 2009, Christopher Savoie, an American-born, naturalized Japanese father, was arrested for allegedly abducting his son and daughter from his ex-wife, who had taken them to Japan illegally. Noriko Savoie had been granted custody on the condition that she permanently reside in Tennessee, but she violated the court order when she took the children to her native Japan. A month later, Christopher Savoie was thrown in jail in Japan on child-abduction charges when he tried to take the children back to the U.S. The case brought global attention to Japan’s failure to endorse the Hague Convention.

When Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited President Obama in February, he reportedly promised that Japan would join the convention on child abductions. “From the perspective of children, there is an increasing number of international marriages and divorces,” Abe told reporters. “We believe it is important to have international rules.”

Joining the Hague Convention will not immediatelyaffect divorced Japanese couples, but it may play a significant role in the transformation of Japanese society and family law.

“We recognize that even if the Hague Convention is ratified, we will have to make many changes in our domestic laws to be consistent” with the convention, councilor Mayama said in a press conference held last week. “At least the Japanese government recognizes these problems. We Japanese have a very traditional view of the family system. It may take time for these changes. We are working on the necessary legislation. Japan will try to make a change in the domestic laws by March of 2014.”

When international marriages break up, Japanese courts almost never grant custody to foreign parents, especially fathers. However, Japanese parents can also come out on the wrong side of the law.

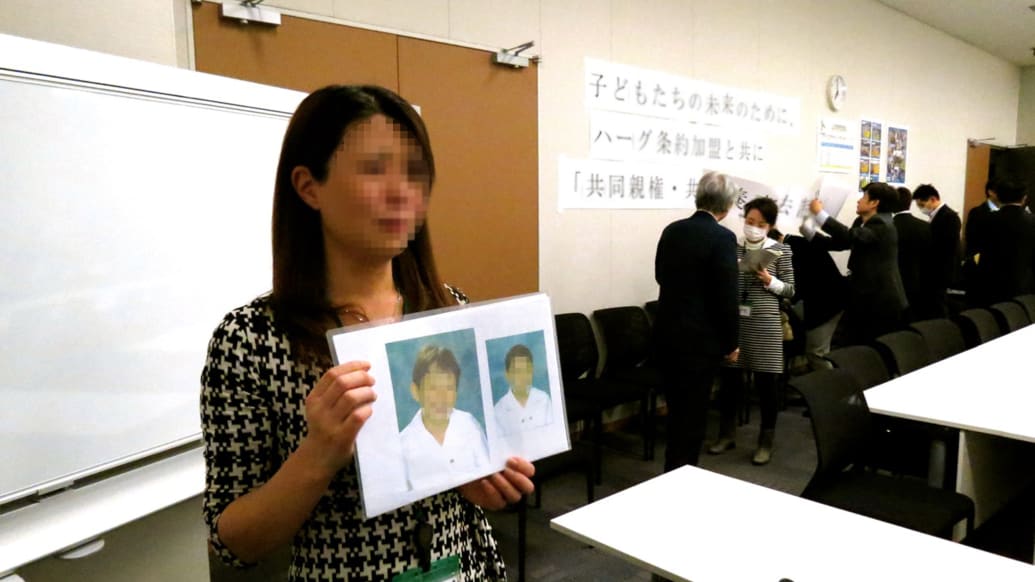

Mika Chiba, 42, works as an accountant and she lost custody of her two sons. Shortly thereafter, her husband took their children to Manchester, and she followed him there and took him to court.

The U.K. court, citing the Hague Convention, ruled in April 2011 that Chiba’s husband had illegally abducted their two children, and therefore the family should return to Japan to decide the custody of the children in a Japanese court. The family arrived in Japan two months later, and the custody battle is currently being fought. But because there is no joint custody in Japan, and because of her nine-month absence when she was hospitalized, the children have been placed with their father, and Chiba lost visitation rights after she quarreled with her husband in July 2011. She hasn’t spent time alone with her children since then.

“I think the Japanese laws should be changed to discourage abduction and allow joint custody,” Chiba said. “If both parents could look after their kids after divorce, then there would be less abduction or maybe none. I think this is the problem in the Japanese law.”

In early February, we followed a French-speaking national, who asked not to be identified, when he visited Japan hoping to meet with his daughter. He does not have custody of his child, nor did the Japanese courts grant him visitation rights.

He went to her home, but was told by his former mother-in-law that she wasn’t there. He then tried to visit her at her school the next day. He asked the school’s principal if he could give her a waterproof camera he had bought for his daughter as a birthday present. “Sir, in Japan, the child has no right to choose if she can see her [noncustodial] parent, after a divorce,” the principal said. “If I handed this present to your daughter without the consent of your ex-wife, I could be in trouble” with the police. He waited for seven hours near the school before going back to the airport and was not able to speak with his daughter or even catch a glimpse of her.

“I don’t want to fight the Japanese authorities, because it will not help me see my daughter. I cannot win their confidence if I do the bad things,” he said. “I hope my daughter will not forget her father and, when she will become an adult, she will try to find me, because she will look for her other cultural roots.”

He hopes that the ratification of the Hague Convention may spur changes in domestic law that will allow him to have some role in raising his daughter. But his hope may be misplaced.

“I think that it will be difficult to convince the hardheaded lawmakers” to fully honor the convention,” said Tsuyoshi Shiina, another Diet member. “They believe it is a matter of ‘cultural conflict.’”

Prof. Takao Tanase also believes that Japan will ratify the convention, but not fully implement it. “Japan fundamentally supports current family-law practices. That’s why there is a strong discrepancy between the domestic law and the international standards, and that will impact negatively upon the implementation of the convention in good faith,” he said. “If the Hague Convention is ratified, and foreign nations recognize that Japan really does not comply with it, there should be a lot of pressure and criticism from the international community. I am hoping that it is the international pressure that is going to push Japan into really implementing the convention.”

It seems certain that Japan will finally sign the Hague Convention, but the implementation of it may take a very long time. Parents waiting in legal limbo to be with their children hope that it will not take another 30 years.

Editor’s note: After publication of this article, Mrs. Mika Chiba requested that her children’s names and images, as well as some details of her personal history, be removed due to safety concerns and The Daily Beast has updated the original version of this text.