Thanks to sole custody, limited visitation and weak courts, kids are often estranged from one parent. But opponents of reform say some proposed changes could make matters worse.

By

January 24, 2023 at 10:00 PM GMT+2

Yasuo Hojyo was home alone when his wife and five-year-old son appeared in the doorway. He said the boy seemed troubled. “My son was looking at my wife uneasily. He looked confused,” Hojyo said.

When he returned from work a few days later, they were gone. Inside was a letter from a lawyer saying his wife had filed for divorce.

That was almost a year ago. Since then, Hojyo, 49, has been living alone in the two-story house in Saitama Prefecture, just north of Tokyo, stewing over being unable to see his child, who has since turned six. Hojyo said he’s become so distraught that he avoids going to a local park. “It’s really painful to see children close to my son’s age,” he said. “It’s hard to breathe.”

Hojyo is seeking custody or at the very least visitation. But under Japan’s current legal system, his prospects are limited. He’s one of almost a dozen parents of Japanese children Bloomberg News spoke with, both men and women, who not only lost access to a child after a separation, but are caught in the gears of an opaque family law system shaped by more than a century of contradictory priorities.

In Japan, child welfare in divorce often turns on single-parent custody, where one parent can be largely excluded from a child’s life. It’s an outcome that makes marital breakups all the more fraught in a country where getting divorced is relatively simple and the power of family courts to enforce visitation orders is limited.

Among Group of Seven nations, Japan is alone in not recognizing the legal concept of joint custody, or “shared authority.” While the majority of Japanese divorces settle privately or are successfully mediated, courts take over when spouses can’t agree, eventually awarding the equivalent of full custody to one parent if there are children involved. Parents secretly moving out and taking children with them isn’t unheard of—in fact, it’s often viewed in Japan as justified, in part because of instances where domestic violence is alleged. Such unilateral separations are legal in Japan, but if the other parent attempts to take the child back, that can be considered an illegal removal.

When custody fights do reach the courts, the mother generally wins full custody (in Japan, the custody concept is split into physical custody—defined as day-to-day care—and a type of legal custody that gives a parent say in big decisions like medical care and residency). The parent who loses the court fight often becomes estranged from the child, as court-ordered visitation is sometimes limited to a few hours each month.

But this state of affairs may soon change. A landmark proposal to make the system more like that of other nations—including the potential adoption of a legal joint custody system—cleared a major hurdle in November, part of a controversial review of Japan’s child custody laws.

Proponents see such reforms as key to addressing broader dysfunction within Japan’s legal system while potentially conferring profound social and economic benefits. Opponents of joint custody warn such changes may have unintended negative consequences, especially when it comes to divorces where allegations of abuse are leveled.

One thing both sides agree on, however, is that more state intervention is needed.

“Parents thought it was inevitable that they would not be able to see their children after divorce.”

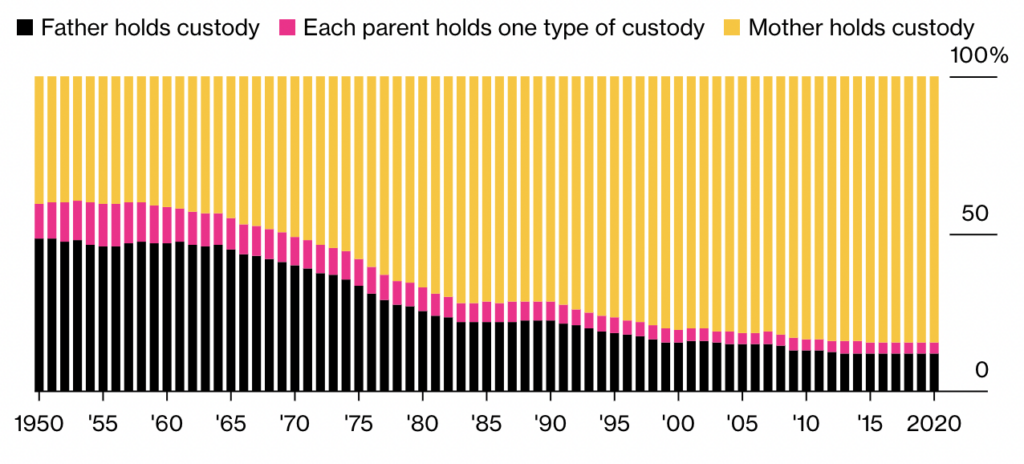

In the first half of the 20th century, child custody in Japan was almost always granted to fathers while divorced mothers were pressured to return to their original family home. The practice stemmed from “Ie seido,” a 19th century system that institutionalized a patriarchal family structure.

But after World War II, the sole custody system was introduced as courts moved toward placing children with primary caregivers. As Japan’s economy expanded 55-fold between 1946 and 1976, the rise of “salarymen” with white-collar jobs and crushing hours coincided with benefits such as tax deductions that tended to encourage women to stay home, or have only part-time jobs. Female employment dropped and maternal custody jumped—but more of those mothers would struggle to get by, thanks in part to weak enforcement of child support laws.

Japanese Mothers Are Winning Custody More Often

The percentage of children residing with mothers after divorce has risen to 85%

Source: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare

In recent years, sole custody has come under increasing fire as the Japanese workplace undergoes a slow transformation from its 20th century structures. Group lawsuits by separated parents seeking more access to their children have increased. “Traditionally, parents thought it was inevitable that they would not be able to see their children after divorce,” said Takeshi Hamano, a sociology professor at the University of Kitakyushu. “But many people can’t tolerate it anymore.”

In November, Japan’s Family Law Subcommittee—tasked by the government to address this historically thorny issue—included joint custody as a potential reform in its interim report. The panel also said mandatory child support and streamlined processes for seizing assets from delinquent parents should be considered as well. The potential changes wouldn’t go as far as other developed nations, but in Japan they would be the equivalent of a legislative thunderbolt.

In setting the committee’s mission in February 2021, then-Justice Minister Yoko Kamikawa cited the system’s collateral damage of unpaid child support and parental exclusion. But experts contend joint custody is unlikely to be a silver bullet for factors underlying custody disputes, ranging from ineffective law enforcement when it comes to domestic violence and persistent gender inequality.

Each year, divorce affects roughly 200,000 Japanese children, double that of 50 years ago in a country where the total number of minors has plummeted. Of children with divorced parents, one in three said they eventually lost all contact with the noncustodial parent, a 2021 government survey showed. Given the system’s winner-take-all approach, spousal battles have only intensified, escalating the economic and emotional damage.

“In Japan, there’s just not a lot of acknowledgement about how much losing a parent could hurt a child emotionally,” said Allison Alexy, an anthropologist who has lived in Japan on and off since 1993 and written a book about Japanese divorce. A 2018 analysis of 60 studies over the past four decades concluded children subject to joint custody had better outcomes of psychological and physical health.

“Under Japanese family law, each family is seen as being responsible for their own matters and the state shouldn’t intervene. Divorce disputes are expected to be resolved internally,” said Masayuki Tanamura, a member of the subcommittee. The current system “doesn’t reflect the needs of modern society. We need systems that work for different family and parent-child relationships.”

But Tanamura warned that revising custody law without expanding financial support for single-parent families—including securing and enforcing child support—will turn out to be “a boondoggle.”

Joint custody “is expected to contribute to the long-term growth of the Japanese economy.”

Over the last 40 years, the number of single-mother households in Japan rose by 46%, but only 28% of those households consistently receive child support. And when they do, the amount averages 50,485 yen (about $386) a month. Overall, child support accounts for 16.2% of total income of single-mother households, according to the government. Failure to pay child support has contributed to the nation’s high relative poverty rate among single-parent households—the worst among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

Indeed, one in two children in single-mother households in Japan face relative income poverty.

“Pre-single mothers face the most challenges,” said Junko Miyasaka, a research fellow at Showa Women’s University, referring to women who are separated but not yet divorced. While the majority of them either hold a part-time job or are unemployed, they are unable to benefit from welfare programs for single parents since they are still legally married.

Yuki Masujima, a senior economist for Bloomberg Economics, contends a system allowing for joint custody would be good for Japan’s economy, increasing living standards and levels of schooling. When it comes to education, he said children of single parents in Japan face bigger challenges than those in other OECD nations.

“The additional financial burden will be limited,” Masujima said of joint custody, “and it is expected to contribute to the long-term growth of the Japanese economy through the accumulation of human capital.”

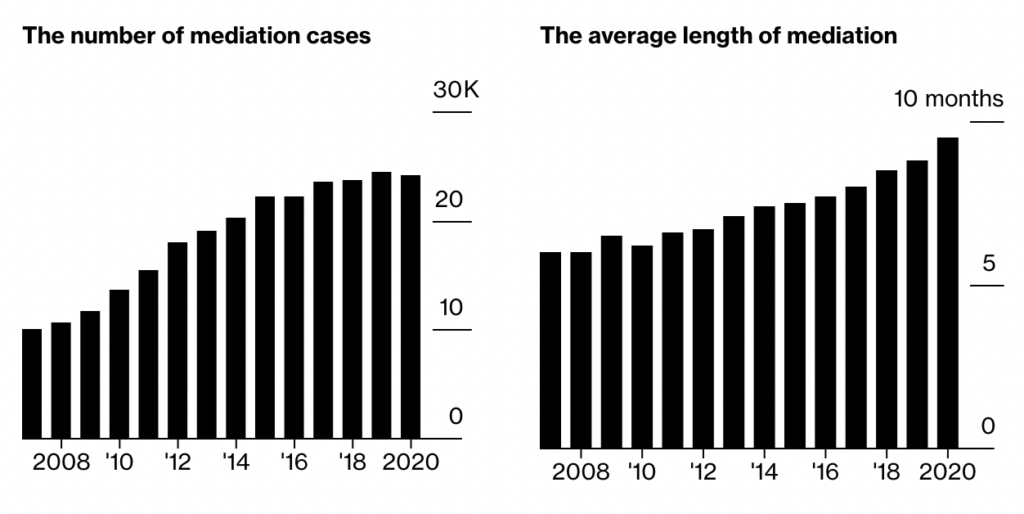

And perhaps more importantly, such reforms could limit the damaging fallout generated by the current system. Japanese parents are competing more fiercely than ever over custody and visitation. In 2020, the number of mediation cases seeking legal custody, return of a child or visitation were more than double those of 2007, according to a Japan Supreme Court report. The average length of mediation reached almost 10 months, a record high.

Custody Fights in Japan Are on the Rise

Disputes over legal custody, return of a child or visitation have more than doubled since 2007 while also getting longer

Source: Supreme Court of Japan

Part of this increased litigiousness may be related to changes both in Japanese families and the workplace. The share of male workers who work more than 60 hours a week dropped from 22.4% in 1990 to 8% in 2020. Over the past five years, the percentage of fathers who take paternity leave tripled to 14% (thanks in part to more generous childcare leave policies), though women still spend 4.5 times more time on housework and childcare.

Still, as more Japanese men play a bigger role in parenting, more are fighting for custody when divorce occurs.

Hojyo is one of those men. After graduating from college in 1996, he went to work as a road maintenance and infrastructure technician. In 2012, he and his wife married. They had their son few years later.

Last summer, after nine years of marriage, the couple began mediation, a process by which courts help guide couples to agreement on divorce, custody and visitation. In a report issued in September, family court investigators pointed to “rejection and distrust” of Hojyo by his son.

“The child strongly wishes to live with his mother,” they wrote, according to a copy of the report provided by Hojyo. The investigators said the mother had been the son’s primary caregiver and that no major problems with parenting had been found after they moved out of Hojyo’s house. Two main reasons cited for the mother to retain custody were continuity of living environment and the son’s desire to live with her. The report did caution however that small children tend to react negatively to the non-resident parent.

Hojyo’s wife declined to comment. Their mediation case ended without agreement and Hojyo said he may pursue other legal avenues. But he fears his son will be completely alienated from him by the time the dispute is over.

“Once visitation proceedings have started, it can be half a year or even several years before the other parent can see their child, and their relationship will be damaged during that time,” said Tamayo Omura, a lawyer in Kanagawa who handles custody disputes. “There needs to be a system to allow parents to keep seeing their children as soon as they’re no longer living together.”

“What does having a judgment from the family court mean in Japan? In the end, not very much.”

If a parent relocates with a child and refuses access to the other parent, it’s “really difficult” to recover that child under the current system, said Tomoshi Sakka, a lawyer who represents parents in custody lawsuits. According to Supreme Court data, there were about 1,000 orders issued over the past decade where a parent requested a child be removed from a spouse. Only one third of them were successful.

Such orders aren’t enforceable the way they are in other countries, said Professor Colin P.A. Jones of Doshisha University. Agencies and institutions generally don’t have to comply. “What does having a judgment from the family court mean in Japan?” Jones said. “In the end, not very much.”

Justice Minister Ken Saito declined to comment on criticism of Japan’s child custody system. A spokesperson for Japan’s Supreme Court said the system is required by law to seek the best interests of the child when deciding visitation and financial support, and that issues related to child safety—such as domestic violence and child abuse—are important factors in determining visitation.

But the spokesperson added that court orders must be carried out without endangering the physical and mental health of the child, and that many aren’t enforced because of resistance from the child, the grandparents or the parent. Parents who have moved away during a divorce or custody dispute, along with their advocates, often cite safety as a prime motivating factor.

“The consequences of joint custody on women and children would be disastrous.”

The prevalence of domestic abuse allegations in marital splits is a critical reason some oppose joint custody reforms.

While a majority of the Japanese public supports joint custody in principle, opponents contend allegations of child abuse aren’t thoroughly investigated before custody or visitation decisions are made. Often, women who leave with a child are escaping an abuser, they said. Joint custody may only make that worse.

The number of allegations of intimate partner crime has risen five-fold since 2001, with women accounting for 75% of the victims, according to the National Police Agency. Some mothers were compelled to carry out visitation after claims of psychological abuse by their husband were dismissed during mediation, said Chieko Akaishi, who heads an advocacy group called Single Mothers Forum.

“The consequences of joint custody on women and children would be disastrous,” she said. “For women being chased by an abuser, such a system would put them in danger for the rest of their lives.” Another aspect of domestic abuse often alleged in Japanese divorces is economic. According to Supreme Court data, a common reason cited by women is “ financial bullying,” where husbands exercising complete control over household finances deprive women of sufficient funds.

Japanese courts have been getting better about more rigorous assessments, including conducting multiple interviews of parents and children, said Yasumitsu Jikihara, a former family court investigator. But he added that a general lack of court resources means “it’s still difficult to assess domestic violence risks.”

Some of the highest-profile challenges to Japan’s child custody system have been by foreign-born parents. Catherine Henderson is one of them. A high school teacher from Australia, she met her now-former husband in Melbourne in 1997. They married, moved to Tokyo and had two children. She said her ex-husband told her on their 15th wedding anniversary that he wanted a divorce.

Henderson, 52, alleged that he eventually left with the children and refused her access. She sought mediation, proposing a parenting plan and visitation schedule, but it went nowhere, she said. Custody of both children was granted to her ex-husband and her appeal was rejected. Her former husband declined to comment.

Henderson, who said she hasn’t talked to her children in three years, finds it “very stressful” to live in Japan, but intends to stay as long as possible, hoping something will change. Almost two years ago, Henderson said she saw her daughter on a train, but didn’t talk to her out of fear she would confuse her. “I’m scared and they are scared,” said Henderson. “I just got off.”

Japan used to be labeled by the West as a “safe haven” for parental abduction. In 2014, after years of diplomatic pressure, it became the last G7 nation to join the 1980 Hague Convention, which provides a return mechanism to deal with international parental abduction. Since then, Japan has aligned with other nations when it comes to international abduction, said Yuko Nishitani, a law professor at Kyoto University.

But for Japanese parents trying to navigate custody and visitation disputes, the disparate treatment looks increasingly unfair.

Hojyo found the slow pace of mediation especially painful. Almost a year later, he doesn’t go to the second floor of his house, where his wife and child lived. “It hurts,” he said. “I almost never go to the second floor. Probably just twice since my wife left with our child.”

“As a father, I want to see and feel my child’s growth. I want to spend my life with my child,” Hojyo said. “If I get to see my child, I just want to chat about anything. If I get to see him on a periodic basis, I want to take him to places he likes, like a baseball stadium and on a fishing trip. He used to like Ultraman. I wonder if he still does.”